In a St. Thomas catechism manuscript from the period 1842-1847, pastor H. Wied has written on the title page ‘In the 1840s, the Creole language disappeared in the West Indian islands and was replaced by English.’ But that didn’t happen. In 1871 and 188/1887, publications by the American scholar Addison Van Name and the Danish physician Erik Pontoppidan were published, still containing some remnants of Virgin Islands Dutch Creole, or Carriols as we call the language nowadays.

In 1883, the Austrian Hugo Schuchardt, perhaps the first linguist we can call a creolist, received a letter from the Virgin Islands physician Anthon Magens. It was a response to a request for a fragment in the Dutch Creole as spoken by the population of St. Thomas. Only in 1914 this letter, filled with words unknown from eighteenth-century sources, was published in the Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsche Taal- en Letterkunde. On May 28, 2022, I published an episode about this letter, ‘The Letter of Anthon Magens’ in my podcast Di hou creol. (10. De brief van Anthon Magens)

The letter that Schuchardt received from Magens in 1883 turned out to be the first comprehensive account of the Dutch Creole as spoken by the local population of the Danish Antilles, St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix.

Carriols as sources dating back to shortly after the language’s emergence. In 1672, the language did not yet exist, it is first referred to in 1736, and since 1739, there have been written texts in this language. However, the vast majority of these texts consisted of translations of missionary texts by German and Danish missionaries. In my research from 2017, I attempted to find clues about the actually spoken Creole in these texts.

Anthon Magens, a distant relative of Jochum Melchior Magens, who published a grammar of the Virgin Islands Dutch Creole in 1770, stated in a letter to Schuchardt that he recorded the daily language with the help of his maid. After a description of a day in the Creole, with many words for vegetables for example and a series of proverbs, follows a so-called ‘pistarkel’, a spectacle that the doctor would have experienced in the streets of Charlotte Amalia. Schuchardt’s publication is in German, but the Creole has been translated into Dutch by Dirk Christiaan Hesseling, who dedicated a substantial publication to the language in 1905.

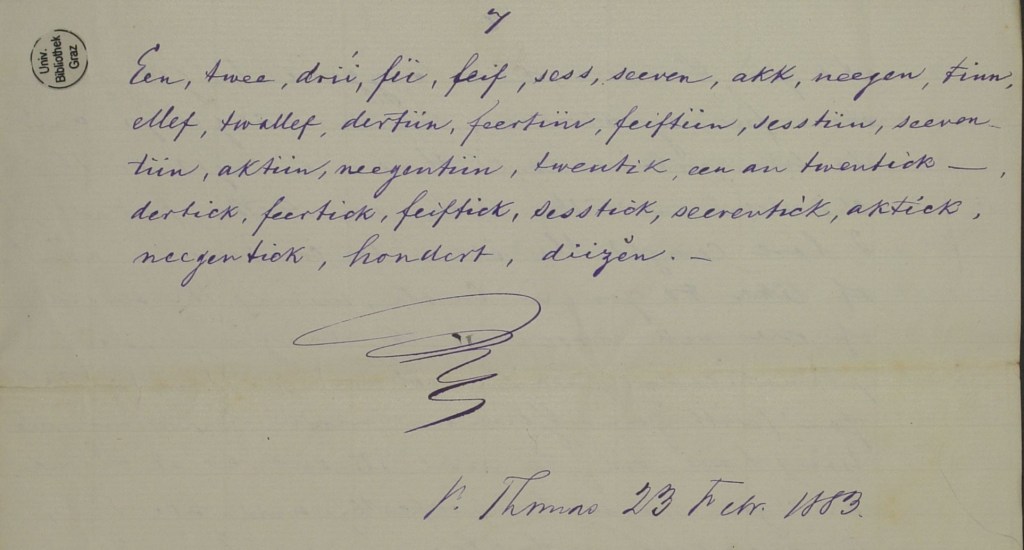

The complete letter is preserved in the archive of Hugo Schuchardt in Graz, and for instance, Peter Bakker, who is currently leading a significant research group on the Virgin Islands Dutch Creole in Aarhus, and his student Sebastian Dyhr, had studied the letter some years ago. Through Sarah Melker, the archivist of Schuchardt’s archive, I received photos of the letter. There is hardly any difference between the letter and its publication in 1914, except for one part on page 7: the numerals.

Why wasn’t this part of the letter published by Schuchardt? Didn’t he consider it of importance? I think it is a valuable addition to the rest of the Creole texts.

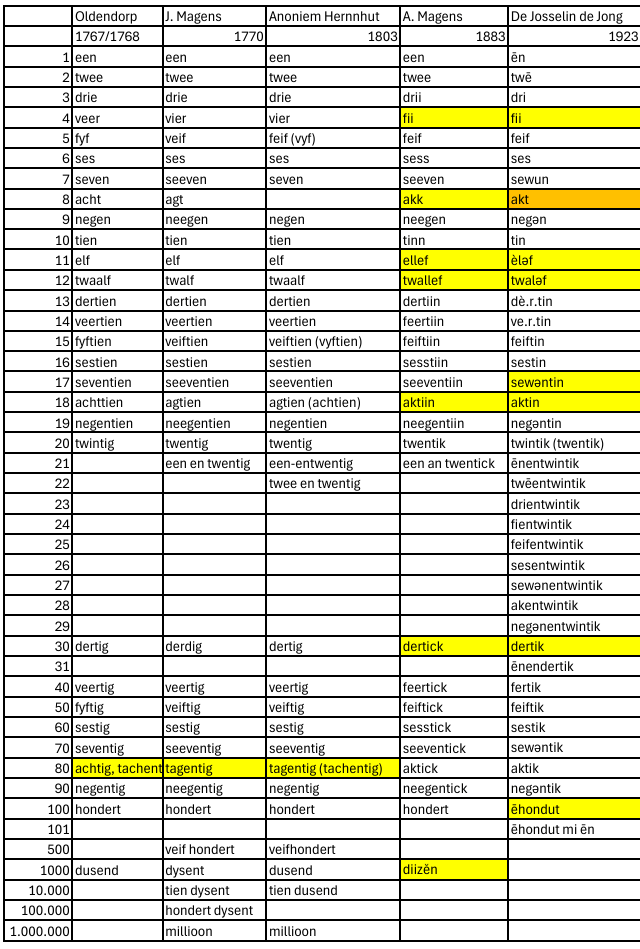

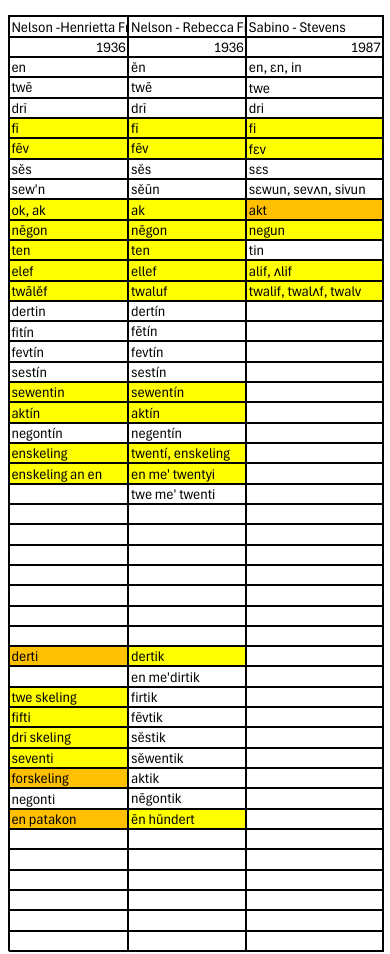

Already in 1767/1768 Oldendorp published numerals in his dictionary (Stein 1996). In Magens’s 1770 Grammar the list is even longer and an anonymous Moravian Grammar copied Magens’s list with some changes. These list were probably necessary for the translations of the missionary texts and look quite Dutchlike.

The numerals as used in the wordlists and texts by De Josselin de Jong (1926), Nelson (1936) and Sabino (2012) look not as bookish as the above mentioned. Of course these were collected during field work in conversations. It is nice to see the numerals from the Magens-letter do show not only Dutchlike numerals, but also the more Creolelike ones which are similar to those which were collected by De Josselin de Jong, Nelson and Sabino.

In this figure you will find all numerals from the above mentioned publications. De Josselin de Jong (1926) mentions his informants, however it is unclear who submitted these numerals and whether these were from St. Thomas or St. John. Nelson (1936) collected two sets of numerals, by Henrietta Francis (Fredriksted, St. Croix) and Rebecca Francis (St. Thomas). Robin Sabino learned the language from Alice Stevens in the 1980s. I used her dictionary from Sabino (2012).

The yellow words are remarkable. See for instance the words for 80. In 1767/68 both achtig en tachentig are used. Tachtig is as in Dutch tachtig, of which the t may be explained from Old Saxon antathoda. In the words for 80 which were recorded during fieldwork, no initial /t/ is found.

We can also see the final /g/ changes during time into /k/ (achtig (80) -> aktik) or it disappears, like in other numerals: dertig (30) -> dertik -> derti).

Henrietta Francis (St. Croix, 1936) used some forms which point to a a kind of twenty-based system, in which the word enskeling is used for 20, twe skeling for 40, dri skeling for 60 and forskeling for 80. In historical Dutch schelling indicates a 20th part of a pound (see Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal). The word en patakon, she used for 100 is also interesting. It was used in historical Dutch, but is etymologically related to Iberian languages.

I haven’t checked the use of numerals in the eighteenth century missionary texts, like the Old Testament or the Gospel Harmonies yet. However, it is already clear that the list from the Magens-letter is an interesting link between written Carriols of the eighteenth century and the spoken variety of the twentieth century.